People that idolize, uncritically follow, or defend psychospiritually stagnant leaders and institutions at all costs—even in the face of clear ethical failure and psychological underdevelopment—they are usually psychospiritually stagnant themselves. So, rather than expanding their capacity for more knowledge, wisdom, and understanding, they outsource their thinking to “authority” figures and societal institutions that mirror their own avoidance of personal growth and inner examination. This means that instead of engaging in self-reflection, refinement of their character, and learning how to think for themselves—where questioning their beliefs, tolerating the discomfort that comes from having their assumptions challenged and their self-image disrupted, and developing personal discernment outside of any external authority and group approval that may be keeping them in a state of arrested psychological development—they remain psychologically dependent on these leaders and institutions that validate their avoidance, that shield them from being held accountable to their own lack of inner ethics and ethical standards, and that reinforce a static identity that never requires them to self-correct, refine their behavior, evolve their sense of self, or take responsibility for their own inner lives.

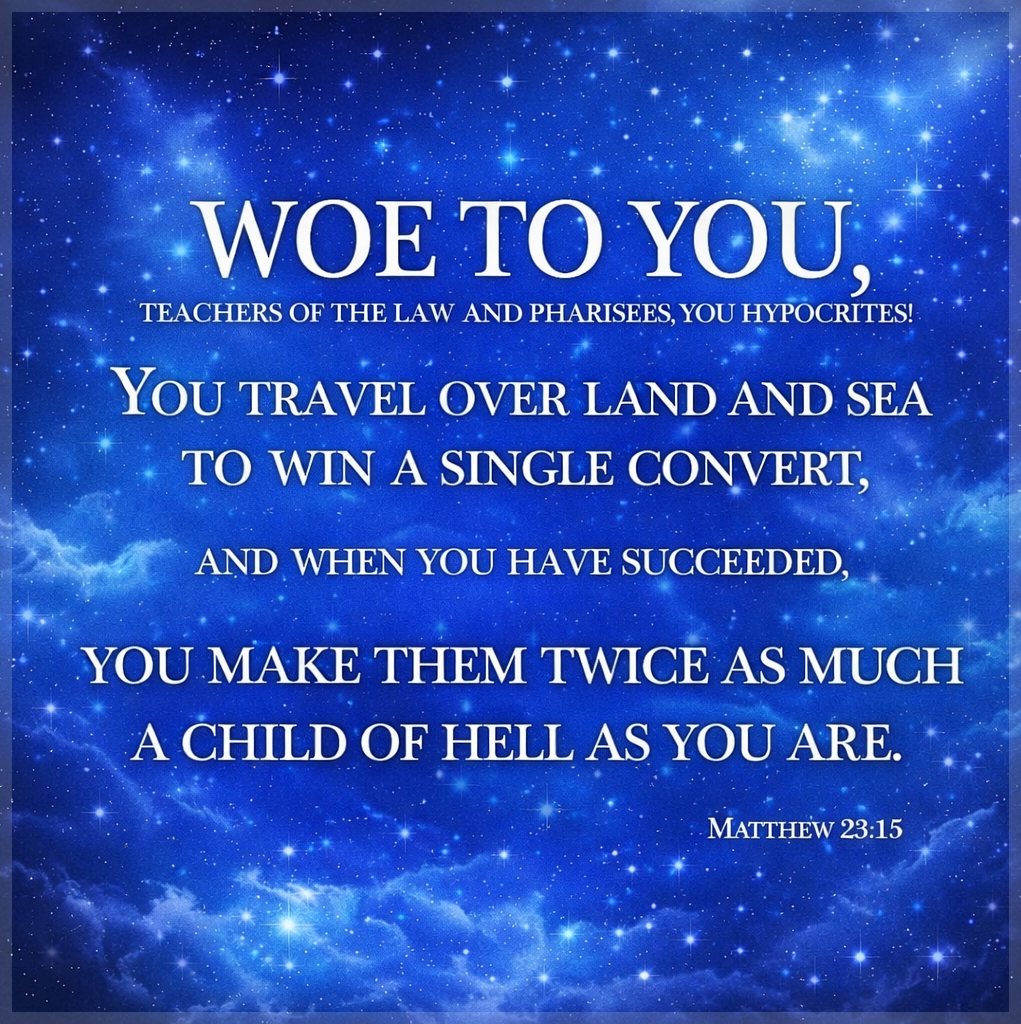

I cannot emphasize enough just how much leadership and societal institutions that are stagnant in intellectual development, ethical reasoning, and capacity for critical self-examination can hold us back from our own potential in our own processes of inner transformation, individuation, and discernment, because many people go their entire lives existing in a state of psychospiritual stagnation, all because they have completely attached their identity to leaders, institutions, belief systems, and rigid ideological frameworks that keep them from ever truly examining themselves, thinking independently, or evolving beyond what they’ve been told to be. This is most likely because, from an early age, their psychological and spiritual sovereignty was taken away from them, where the external world—through authority figures, social conditioning, and inherited belief systems—trained them to equate uncritical obedience to authority with safety, absolute conformity to group norms and expectations with belonging, and unquestioned submission to external authority with moral goodness, leaving them ill-equipped to trust their own judgment, develop independent discernment, or claim authorship over their own inner lives, where they lack the substance of a true, authentic self that has been consciously formed through self-examination, ethical responsibility, and lived self-authorship, rather than just being a composite of inherited identity, unexamined conditioning, and external approval.

I mean, yes, of course we can say that all of this transpires within a grand generational mechanism of conditioning and socialization, where patterns of obedience, fixed identity programming, and moral outsourcing are passed down and normalized long before individuals ever even have the language or agency to question them—but acknowledging that context does not absolve anyone of the responsibility to interrupt those inherited patterns. Because at some point, to reclaim their own inner authority, examine what they’ve inherited, and choose whether or not they will continue reproducing stagnation of consciousness or to begin the difficult work of conscious self-authorship, a decision has to be made. And that decision requires embracing inner transformation, developing discernment, growing in one’s capacity for independent thought and critical reasoning, and then practicing self-governance outside of coercive authority structures, inherited belief systems, and other pressures to conform in order to belong—pressures that are reinforced through things like nationalistic identity constructs, religious dogma, family systems rooted in control and conformity, low-conscious political ideologies, or other socially sanctioned frameworks of identity enforcement and behavioral compliance that discourage independent thought and intellectual maturation—where not choosing to do that work, it becomes an act of avoidance of personal growth, and choosing ignorance, ethical cowardice and moral abdication.

But back to leadership and institutional authority structures that reinforce a static identity, where within these authority ecosystems, stagnancy of psychological development and ethical avoidance are normalized and rewarded, I would say that in this day and age of unprecedented access to information, education, and historical insight, it is an extreme embarrassment for people to continue outsourcing their thinking to “authority” figures and societal institutions that discourage critical examination of power structures, moral narratives, and inherited ideological conditioning, when the tools for independent inquiry, ethical reflection, and self-directed understanding have never been more accessible—and that choosing not to use them is no longer ignorance, but willful abdication of personal responsibility. And that choosing not to critically examine oneself and the systems one aligns with, whether one is operating from unconscious conditioning, willful ignorance, or a conscious embrace of these stagnant systems and authority structures, reveals a profound lack of personal integrity, substance of character, higher-order thinking, and ethical seriousness either way.

So, for those who are actually willing to do the work—to question what they’ve been handed, to examine their own beliefs and alignments honestly, and to take responsibility for their inner development—this path will naturally place them at odds with stagnant leadership, rigid institutions, and authority ecosystems that depend on absolute obedience, unexamined conformity, and a lack of intellectual growth to survive. And that tension is not a failure or a flaw; it is a sign that one is no longer willing to sacrifice their integrity, discernment, or inner sovereignty in exchange for the comfort, approval, or false security that these systems offer but can never genuinely provide. This is because it all comes at the cost of our own capacity for independent thought, ethical self-governance, and authentic inner development—leaving us psychologically dependent, intellectually stagnant, and disconnected from the deeper substance of our own soul, where we are then expected to submit to and sustain leaders and institutions that are themselves stagnant in consciousness, and to normalize, excuse, and uphold the very systems that rely on an avoidance of growth, accountability, and self-examination to survive.

But ultimately, when conscience is placed above comfort, the question is not whether these systems with leaders that are psychospiritually stagnant exist—because they clearly do—but it is whether we will continue to lend them our energy, obedience, and identity at the expense of our own inner development. And that refusing to participate in psychospiritual stagnation—which means withdrawing our compliance, reclaiming our discernment, and refusing to outsource our moral and intellectual agency—is not arrogance, rebellion, or defiance on our part; it is actually an expression of taking responsibility for one’s own conscience, capacity for critical thought, and intellectual development, a commitment that grows out of personal responsibility and an increasingly self-directed inner life. And once that responsibility is claimed, we choose to live as sovereign, independent thinking, self-governing human beings rather than as compliant extensions of stagnant authority figures and institutions that are consciously underdeveloped, meaning they operate from rigid ideological frameworks that are resistant to self-examination or growth. In doing so, we recognize that this is the necessary step of outgrowing systems that cannot support—or that simply refuse to engage in—intellectual growth, ethical development, or critical self-examination.

And while that choice to think independently and withdraw from unexamined systems of authority may cost us a sense of societal approval, social belonging, or perceived safety, it preserves something far more essential to our humanity, which is the integrity of staying true to one’s own conscience, the capacity for genuine inner transformation within ourselves, the development of intellectual depth and critical reasoning, and the responsibility of consciously authoring who one becomes, outside of unquestionable systems of authority and inherited ideological conditioning that has only stunted our psychological, emotional, and ethical development in the long run.