Can “freedom” in this world be untied from human sacrifice (as in the energetic exchange of human suffering for perceived liberty, dominance, or survival)? Or will they always be intertwined? And that at the end of the day, every people, institution, ideology, or nation where human suffering is the byproduct of their pursuit of freedom, order, expansion, or preservation, will always be rooted in a deeper undercurrent of human darkness—no matter how noble the narrative, polished the public messaging, or righteous the cause appears to be. And that the shadow of the human race—its willingness to sanctify domination, to trade lives for both influence and autonomy, and to veil the brutality that takes place in pursuit of those things in moral euphemisms, political virtue-signaling, and carefully scripted appeals to collective good—will always exist. And that maybe, no matter how much light we strive to embody as a species, a force of darkness will always be there too—present, ancient, and unyielding—woven into the very fabric of what makes us human beings.

And then if that’s true, next comes the question: Is human sacrifice and the suffering of others morally gray? Neutral? And if every country, nation, ideology, or belief system that partakes in human sacrifice or causes human suffering on some level through their own efforts of preservation, expansion, self-determination, or perceived justice believes it is justified—then at the end of the day, we must reckon with the unsettling reality that humanity has collectively agreed, whether consciously or not, that it is acceptable for human beings to sacrifice other human beings in the name of perceived freedom, survival, or moral authority. And no matter how much one may believe their country, system, or ideology is righteous in its own rituals of violence (while hypocritically demonizing others for doing the same for their own freedom, survival, or sense of sovereignty)—in the grand scheme of things, there’s nothing inherently wrong with human beings sacrificing one another or causing suffering to one another—at least not according to the logic this world runs on. Because within that logic, violence becomes relative, morality becomes conditional, and suffering becomes a negotiable cost—so long as it’s framed within the bounds of what each group believes is necessary, noble, or inevitable for its own endurance.

Because if everyone believes that their violence is justified, that the suffering they cause is sanctified, and that their cause is righteous, then what we’re really left with isn’t a moral reckoning, a confrontation of conscience, or any kind of genuine sense of universal accountability—but a tacit agreement between civilizations, nations, belief systems, and identities that blood or human suffering will always be the currency of liberty, survival, and dominance (no matter which people, culture, ideology, or civilization is doing the sacrificing and causing the suffering). And maybe the true horror isn’t that human sacrifice and suffering exists, but that it has become so ritualized, so rationalized, and so embedded into the structures of the human experience—that we no longer even recognize it for what it is—beyond all our sanitized histories, cultural conditioning, the diverse expanse of ideological justifications, or inherited national myths. And that beneath all the denial, deflecting, and repression of what’s actually taking place—it is still, and always has been, the ritualized offering of human lives, literally, or energetically through suffering, submission, and soul-wear—at the altar of national myths, ideological preservation, cultural continuity, and the illusion of justified dominance.

So when looking at the largest possible picture—the one beyond individual ethics, beyond societal programming, beyond good and evil, or frameworks of culturally constructed morality—which are all subjective in their own right—we’re left with the sobering realization that human sacrifice is not just a relic of ancient civilizations, cultures of old, or the shadow of imperial systems. It is, in many ways, a recurring expression of the human condition itself. And maybe, just maybe, it’s not the exception to our humanity—but a reflection of it. And that’s the most sobering realization of all: that to be human in this world, may very well mean being born into a species that runs on sacrificing itself for perceived liberty, domination, or survival—and learning how to live with the weight of that awareness—no matter who is doing the sacrificing, spilling of the blood, or the causing of human suffering through their self-preservation pursuits, even if it’s not in our name as a nation, a culture, an ideology, or a collective identity we personally claim.

And while I’m sure most people would love for those on Earth to get along and peacefully co-exist in the vast expanse of human diversity, the reality is that in this universe, no matter our background, origin, or worldview, the paths we take to preserve what matters most to us often create ripples of consequence for others. And when viewed from a wide enough lens, all groups are justified in their efforts according to their own narratives—even as those efforts inflict hardship on those who live outside of them.

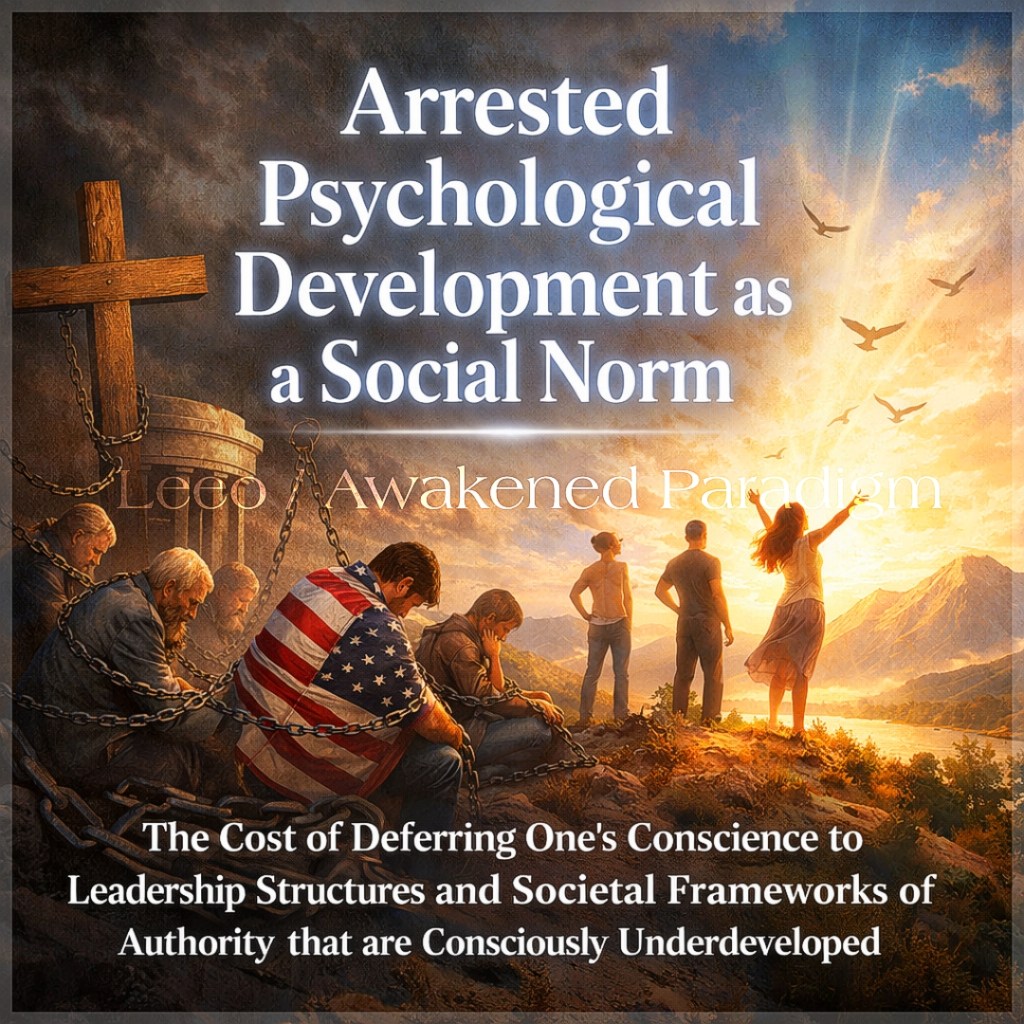

So maybe the deeper reckoning isn’t about whether we can stop human sacrifice, conflict, or the suffering of those outside of our constructed boundaries of what belonging looks like, the subjective morality that changes depending on cultural allegiance or ideological lens, or what we’ve been conditioned to believe is “good” or “of the light.” Maybe it’s about whether we can finally see the human species for what it is—no longer dressing up its violence in moral delusions that soothe the collective conscience of whichever in-group is narrating the story, or repackaging its wake of destruction in the pursuit of order, freedom, or preservation, as a noble necessity—but naming it, exposing it, and understanding it as a core mechanism of how this world functions. Not to glamorize it. Not to justify it. But to confront the uncomfortable truth that human beings, even in all their striving for meaning, order, or righteousness—no matter the system, belief, or identity—are operating in as much darkness simultaneously as much they are reaching for the light (according to whatever metrics their culture, ideology, or belief system has defined as enlightened or morally superior).

And maybe—just maybe—true evolution of our species begins not with the denial of our own capacity to inflict harm in the name of progress, identity, or survival, but with the courage to bear witness to the darkness that lives within us—the primal force that’s woven into the very essence of what makes us human beings—and to ask the questions no one wants to answer: What kind of world are we really building, if it still runs on the suffering of others? And if human suffering is inevitable—woven into the very systems we uphold, into the ideals we chase, and the identities we cling to—then the real question becomes: can we create a world that no longer hides behind righteousness to justify that suffering, but acknowledges it, grieves for every life and dream lost to it, and dares to build something beyond it? Even while that striving remains tethered to the paradox of our condition—where the pursuit of light, no matter what it looks like depending on which country, nation, ideology, or belief system we hail from, is never free from the shadows it casts. And that even while we reach upward according to our own convictions, creeds, or callings, our darkness is taking up just as much space as whatever we each perceive to be the light—moving with us, shaping us, and leaving its imprint on everything we create in our individual efforts to do what we believe is right, just, or necessary.